From science to reality: What approval of cell-based meat means for the industry

Singapore's approval of cultured meat is the beginning of a journey to bring something new to the business and potentially change how the world makes food.

The announcement earlier this month that Eat Just's cultured chicken had received regulatory approval in Singapore took a huge step to legitimize the cell-based meat industry. What was once seemingly science fiction is now something that consumers will be able to eat.

"It opens up the door for all of us to stop talking about things, and actually scale this damn technology and make the world's future meat," Eat Just CEO Josh Tetrick said at a panel at the virtual Future Food-Tech conference days after the approval was announced. Eat Just's cultured chicken bites will be sold under the Good Meat brand at a restaurant on the island nation in the near future.

While the milestone may change how consumers perceive cell-based meat, the work is far from over for some of the companies working in the space. Yaakov Nahmias, founder and chief science officer of Israel-based Future Meat Technologies, said his company is still working on scaling its fast cell growth, high-yield technology. Mosa Meat, which just announced more funding, continues to work toward making enough of its product to seek regulatory approval in Europe, said Chief Scientific Officer Mark Post. And California-based Memphis Meats is busy scaling everything — building up its pilot production facility, team and production capacity, Vice President of Product and Regulation Eric Schulze said in an email.

But does regulatory approval in Singapore truly change the game? Will consumers see cultured meat on menus and in stores sooner rather than later? Are the U.S. or other nations going to be quicker to pull together a regulatory framework for cell-based meat products? And will funding come pouring into the space?

"I do think it changes the perception off the field from other players — you know, media players, pharmaceutical players, suppliers suddenly looking into what we're doing," Nahmias said. "And, we feel that we're going to probably encounter less resistance as we move forward, as suppliers would look at it and say, 'Wait a second, this is real. Now we need to return their emails.' "

The Apollo project of the 21st century

Nahmias, who is a professor of bioengineering at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, started Future Meat Technologies based on his own research. The science focuses on a concept that humans have understood for years: Meat is made of cells that grow and divide.

The science is step 1, Nahmias said. While getting regulatory approval to ensure that a product is safe to eat is profoundly important, it's more of a bureaucratic step, he noted.

Future Meat has concentrated on honing its method for producing more meat in smaller reactors. The cell-based meat race is not about getting a product on the market first, Nahmias has said. It's about getting the end product right.

"The focus needs to be ... how to scale up quickly, inexpensively. How to do it efficiently," Nahmias said in an interview this month. "How do you produce the same amount of mass? ... We are talking about millions of tons a year that we need to be producing if we want to replace, or at least make significant change, in how people around the world are consuming protein."

He compared Future Meat and other cultured meat companies to automobile makers at the beginning of the 20th century. Back then, they created cars to replace horses and buggies, but consumer adoption was relatively slow. While people surely saw cars as a novelty and a way to get from one place to another more efficiently, initial costs were high and supplies were tight. Then came the Model T in 1908. The Ford vehicle was mass produced, relatively inexpensive and accessible to average people. And it's been credited with fundamentally changing life in the United States.

Nahmias said a scalable way to produce meat with a price consumers can afford will help the cell-based sector take hold. And that's what he's strived for. Future Meat has a diverse scientific staff that includes chemists, mechanical and chemical engineers, food scientists, chefs, biologists and interpretational biologists focused on building a new way to get meat.

"I don't know of a single field that has been so multidisciplinary," Nahmias said. "And I've been in pharma and medical devices. ...nothing is even close. Honestly, the closest thing is the Apollo project."

Memphis Meats is also working on scale, Schulze wrote in his email.

"The biggest challenge for the entire industry will continue to be scaling high-quality products that have the capacity to supply not just a single restaurant, but an entire restaurant chain," he said.

"I don't know of a single field that has been so multidisciplinary. And I've been in pharma and medical devices. ...nothing is even close. Honestly, the closest thing is the Apollo project."

Yaakov Nahmias

Founder and chief science officer, Future Meat Technologies

Mosa Meat is at a similar place. The Dutch company was the first to create a cell-based hamburger in 2013. It's come a very long way since then, raising a total of 75 million euros (nearly $91 million) and both building and expanding a pilot plant to make cell-based meat.

Post said Mosa Meat is hoping to first get regulatory approval in the company's home base of Europe, but it's not ready to apply for that just yet. It is still working to make enough of its product to work through the process of the European Food Safety Authority, which requires five production batches.

"The product that we are envisioning, and that we are going to seek regulatory approval for, is sufficiently different from what has been approved in Singapore," Post said. "We basically still have to follow our own route and not be distracted too much by the approval of this particular product."

One of Mosa Meat’s biggest challenges has been creating a product without using pricey fetal bovine serum (FBS) as a growth medium for cells. Most industry players began there, using the substance extracted from cow fetuses to start their cell-growing research. But because of the high cost and the animal source, companies quickly sought alternatives from plants and other sources. Mosa Meat was a pioneer in this approach, partnering with animal nutrition company Nutreco to work toward improving that kind of medium. Its most recent funding, which was announced last week, included money from the arm of Mitsubishi Corp. that deals with feedstocks.

Getting a plant-based growth medium to work efficiently is a main reason Mosa Meat isn't yet working with regulators toward approval.

"You'll never want to produce with FBS, so [we decided] let's not seek approval with FBS. And that's a choice that a company makes," Post said.

Eat Just's cultured chicken approved in Singapore is produced with a low level of FBS, though it is removed from the final product through harvesting and washing, company spokesman Andrew Noyes said in an email. The company has developed an animal-free nutrient base for cell growth that it will use for the cultured chicken once it receives regulatory approval.

The U.S. quest to be No. 2

There is a big reason why Singapore was the first to grant regulatory approval for cell-based meat.

The Asian nation, located on a 223-square-mile island, is among the world's richest countries. Last year, Singapore pledged to be able to source 30% of its food domestically by 2030. It intends to rely on high-tech, small-footprint ways to grow and harvest food. The country's regulators had said they wanted to be the first to get into the cell-based meat space. Post said they had personally invited Mosa Meat to seek regulation there.

But the United States may not be far behind Singapore in getting a regulatory framework in place.

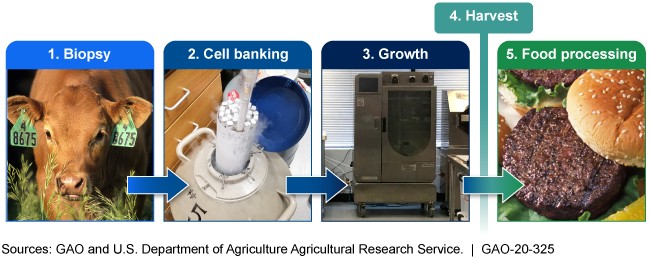

Last March, the FDA and USDA issued a formal agreement to jointly regulate cell-based meat and poultry, dividing the process because of the way products are made and the fact that end products are meat.

While little has been made public since then, the regulators are working behind the scenes. Last June, FDA and USDA created three working groups to hash out the details. One group deals with pre-market assessment, another with labeling and the third is developing a procedure for the transfer of jurisdiction — the point when cell-based products are "harvested" and go from regulation by the FDA to regulation by the USDA.

In May, the U.S. Government Accountability Office published a report on cell-based meat regulation. It zeros in on the process for cultivating these products and the extent to which the agencies are collaborating on regulatory oversight. According to this report, all three working groups are active.

Deepti Kulkarni, a partner at the Sidley Austin law firm, said this is an incredible pace of progress for federal government regulation. She previously worked in the FDA's general counsel office on agency oversight and regulatory pathways for new and emerging technology. After leaving the federal government, she advocated for the dual FDA-USDA regulation of cell-based meat. Her firm is currently working with companies in the cultured meat space.

A decade ago, Kulkarni would not have thought the federal government could figure out how to regulate a brand-new product category in a matter of years.

"If we're reading the tea leaves here, that means that they see some value proposition with respect to the technology, or at least some recognition that this product is going to come to market," Kulkarni said. "Two, they see an interest in it, a real interest in it. Otherwise, what would be the need to move so quickly? And three, they see a pathway for the agencies to regulate."

"They see some value proposition with respect to the technology, or at least some recognition that this product is going to come to market. ...They see an interest in it, a real interest in it. Otherwise, what would be the need to move so quickly? And ... they see a pathway for the agencies to regulate."

Deepti Kulkarni

Partner, Sidley

In an email, an FDA spokesperson told Food Dive this agreement includes a commitment to engage in pre-market consultation with companies seeking to enter the space.

"We are encouraging firms to have these conversations with us often and early," the email says. "We cannot speak to the market plans of individual firms, but the Agency is carefully following developments in this area and is in conversation with a number of firms that have engaged FDA. Our goal is to support innovation in food technologies while always maintaining as our first priority the safety of the foods available to Americans."

At a session at the Future Food-Tech conference earlier this month, Dennis Keefe, director of FDA's Office of Food Additive Safety, said these conversations have been very fruitful. While the companies working on cell-based meat have some things in common, their strategies and technologies differ greatly.

"This helps us to understand where the technology is, so that when we do issue our draft guidance [for regulation], it is more informed by what is actually being done in the development space," Keefe said.

Future Meat has been involved in these conversations with FDA, Nahmias said, noting that the agency has been "very positive." The company has shared data with regulators, who have in turn commented and asked questions. From what he can see, Nahmias thinks FDA may start a formal submission process in the first quarter of 2021.

Memphis Meats has worked with federal regulators as well. Schulze said in his email that as a U.S.-based company, Memphis Meats is focusing its efforts and wants its first products sold here — though it may expand to other countries in the future.

"A big part of our strategy has been to engage early on with key stakeholders and work alongside each of them, including our federal regulators," Schulze said. "A lot of that involves providing information about our products and production process to the folks at USDA and FDA so they can make informed decisions and ensure that the regulatory path is safe, fair and transparent."

Eat Just is also working through the process with FDA, although Tetrick did not elaborate on its status.

Regulatory approval for cultured meat in Singapore is, without a doubt, something of which the FDA and USDA have taken note. But Jonathan Havens, a partner at law firm Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr, said the agencies exist to protect public health, not react to public pressure, and “will be led by their own questions, by their own concerns, and only once those concerns and questions are addressed will those agencies be comfortable moving the ball forward."

FDA and USDA are also working toward making determinations about what the products should be called, which is a major area of contention. FDA, which will be the sole regulator for cell-based seafood products, opened a docket for input on labeling last month. So far, it has received seven comments. In an email to Food Dive, a USDA spokesperson said the agency intends to open a similar docket about meat and poultry labeling "in the near future."

And though a new presidential administration is set to take over next month, attorneys with knowledge of the regulatory process said this is unlikely to make a difference. Most of the regulatory work happens with career staff of the agencies, which work on broader, nonpolitical policies. What could make a difference: how interested agency leadership is in the issue, said Bob Hibbert, senior counsel at law firm Wiley Rein.

"If you get people at the senior level, whether it's FDA commissioner level or undersecretary level at USDA with a certain policy bent, certainly, that can make a difference," he said.

The Biden transition team did not respond to emailed questions about how important cell-based meat regulation was in choosing leadership for USDA and FDA.

A less risky investment

As time has gone on, the interest and money for this space have grown.

There are more than 50 companies only dealing with cell-based meat, according to data collected by Finistere Ventures. (This count does not include Eat Just, which also has a plant-based egg business.) Only one company currently is publicly traded: Israel's Meat-Tech 3D, which is now on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. The rest are privately funded, and collectively have raised more than $440 million, according to Finistere's statistics. They range from relatively large firms such as Memphis Meats, which closed a $161 million funding round in January, to much smaller startups.

Finistere Ventures invested in Memphis Meats last year. Jennifer Place, Finistere's San Diego investment director, said the firm examined cell-based meat, its possibilities and its problems before committing funds.

"A big part of our strategy has been to engage early on with key stakeholders and work alongside each of them, including our federal regulators. A lot of that involves providing information about our products and production process to the folks at USDA and FDA so they can make informed decisions and ensure that the regulatory path is safe, fair and transparent."

Eric Schulze

Vice president of product and regulation, Memphis Meats

There are many risks to investing in this space, she said. There's the potential of high product costs — Mosa Meat's 2013 cell-based hamburger cost 250,000 euros (roughly $280,000 in 2013) to make. Replacing FBS with non-animal-based options has brought that cost down significantly. This summer, Mosa Meat announced that themedium to grow a hamburger is now 88 times less expensive. Tetrick said Eat Just’s cultured chicken bites will have a cost comparable to premium chicken on the restaurant menu where it will debut.

The amount of equipment that is needed upfront to establish a cultured meat business also could be seen as a risk to investors, Place said. The business depends on precise bioreactors, well-calibrated instruments and facilities for safe production. While these may not be difficult to find, they are costly.

Lack of regulatory approval was the third big risk, Place said. Without this, there is no market for products, and a dimmer guarantee of return on investment. Singapore's approval has diminished this risk significantly.

"We certainly believe that having the regulatory validation from this front will attract more investors to the space that were perhaps looking to see de-risking ... to be able to take on the baton in terms of for the next round of capital raise for the space," Place said.

The beginning of the next big thing

Analysts have said this is the beginning of a sea change in how the world gets its meat.

Strategy and management consulting firm Kearney published a report predicting that by 2040, 35% of all meat consumed worldwide will be cell-based. About 40% will be conventional meat, and 25% will be plant-based alternatives. Corey Chafin, a principal in the firm's consumer practice, said this is based on projections that have little to do with the current advances in this field. As it wrote the report, Kearney concentrated on factors including global population estimates, food needs for people and livestock, and resource challenges.

The report indicates that in 2018, the largest chunk of crops harvested worldwide — 46% — went toward animal feed. Human food took just 37% of the harvest. And as the human population is expected to be 10 billion by 2050 — an increase of 2.5 billion from 2018 — food and space needs will increase, but the amount of land will stay the same. The report finds that cell-based meat could solve these problems through efficient production of food that is less resource- and space-intensive.

"Cultured meat is not just a trendy thing that you go try once or twice, but it's actually a pathway to continuing to feed a growing population in certain areas of proteins, where we see animal-based meat being constrained in the future," Chafin said.

But will consumers want to eat meat that came out of a bioreactor? According to a 2018 online survey from PR firm Ingredient Communications, almost three in 10 consumers in the U.S. and U.K. were willing to try the products. A third of consumers weren't sure, while 38% said they would not.

"I hope that the biggest meat companies ... read this and say, 'We're going to get in this now. Now, we're going to turn our attention, our vast capital resources, our infrastructure, our manufacturing prowess, our distribution capacity. And this is how we want to make meat.' Because I think ultimately you need that kind of energy into it if you're really going to change things."

Josh Tetrick

CEO, Eat Just

Chafin said that consumer preferences are likely to shift as price and taste improve. He pointed to the growth of plant-based dairy and meat, which were once curiosities and are now considered mainstream. Many conventional dairy and meat companies have also introduced their own plant-based products. Chafin and Place expect this to eventually happen with cell-based meat.

"They know that there is a plateau in animal-based meat consumption," Chafin said.

Big Food is already backing cell-based meat, with Tyson Ventures funding both Memphis Meats and Future Meat Technologies. Monde Nissin CEO Henry Soesanto has invested in Future Meat Technologies.

Nahmias said this is just the beginning. Cell-based meat minimizes risks around animal illness, weather and raising the right amount of meat to deal with volatile market prices when it is ready to harvest.

"I expect in the next two to three years, farmers and traditional meat companies around the globe will start looking at us and saying, 'Wait a sec. I can do the same thing I'm doing now, but a lot more efficiently. I need to use this technology here,'" he said.

It's inevitable that consumer acceptance will grow, and cultured meat will become dominant in a matter of decades, Tetrick said.

"I hope that the biggest meat companies ... read this and say, 'We're going to get in this now,'" he said. "'Now, we're going to turn our attention, our vast capital resources, our infrastructure, our manufacturing prowess, our distribution capacity. And this is how we want to make meat.' Because I think ultimately you need that kind of energy into it if you're really going to change things."

Correction: The year Finistere Ventures invested in Memphis Meats was misstated in a previous version of this story. Finistere invested in Memphis Meats in 2019.

Quelle: FOODDIVE